The timing is just right. Peter Cklamovski is going to be announced (or maybe he will have been announced after this article comes out) as the new Malaysia head coach, replacing Pau Martí. Malaysia are playing at the ASEAN Cup and I am covering the tournament extensively (which you can find the articles about Malaysia just below). Then, Hudl and Statsbomb have released free data of the 2024 J1 League season.

The stars have aligned and everything is just calling for a deep-dive article about Cklamovski’s 2024 season with FC Tokyo and predict what Malaysian fans will see under his management. It is also a good opportunity to evaluate Malaysia’s current performance in the ASEAN Cup. As it has been over a year since my data deep-dive article about Božidar Bandović, here we go again with another data deep-dive article, this time it will be about Cklamovski and his FC Tokyo side in the 2024 season!

Note: All J1 League data used in this article is from Hudl Statsbomb. Malaysia’s ASEAN Cup data is from Opta. Team and player stats are from the J.League official website and Football-Lab.

Style of play

Having worked under Ange Postecoglou beyond their time at Yokohama F. Marinos and goes way back to Melbourne Victory and the Socceroos, Big Ange has definitely left an impact on how Cklamovski wants his team to play and how they set up. The fact that FC Tokyo started with the 4–2–3–1 formation in 28 out of 38 matches during the 2024 season shows that Big Ange’s influence does have an impact on Cklamovski’s philosophies.

It is interesting to note that Tokyo also started with the 4–4–1–1 formation (1 match) and the 4–4–2 formation (9 matches) last season. This is because both formations can be transformed to from the 4–2–3–1 formation, with the attacking midfielder/#10 moves forward and creates a two-man front line with the striker, or both wingers dropping slightly deeper. But, in overall, while general formations are meaningless nowadays considering how often teams change both with and without the ball during the match, it is possible to say that Cklamovski’s preferred formation is a 4–2–3–1.

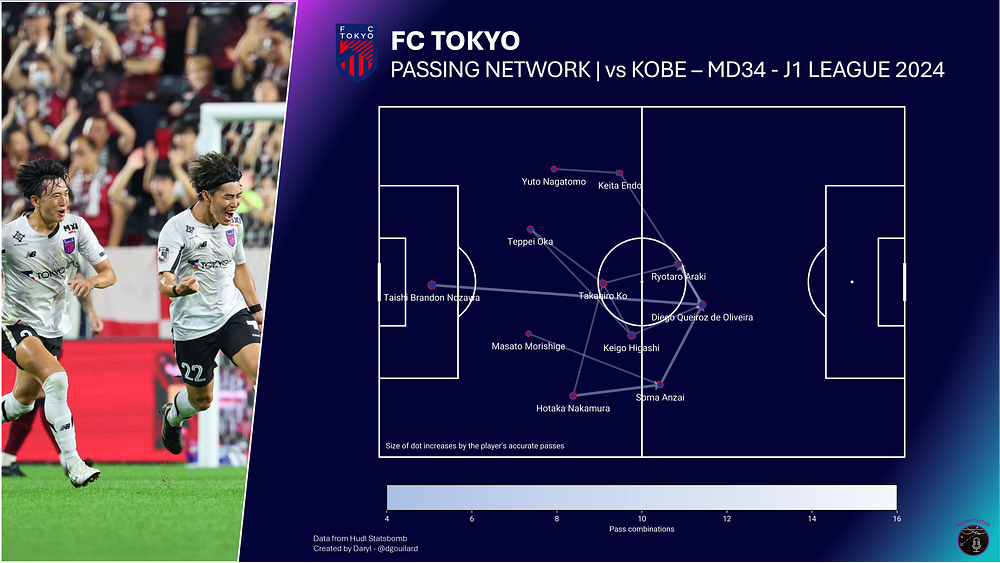

Picking Tokyo’s second clash against Vissel Kobe last season and it is possible to see their 4–4–2 shape formed when the team had the ball. Attacking midfielder Ryotaro Araki played almost next to striker Diego Oliveira while both wingers Keita Endo and Soma Anzai stayed a bit deeper. The average positions can also be seen in a 4–1–4–1 formation considering the central midfielders’ average position. Takahiro Ko played almost like a central #6 even though, on paper, he was supposed to be the left-sided central midfielder. Meanwhile, Keigo Higashi operated a bit wider to the right and stayed higher than his pivot partner.

On paper, the fact that Cklamovski’s prefers to play with the 4–2–3–1 might actually benefit Malaysia since they have started with the 4–2–3–1 in two of their first three matches at this year’s ASEAN Cup. However, the way that they are currently playing under Pau Martí is a lot different than how Cklamovski’s FC Tokyo played.

Granted, the matches that I picked to visualise Tokyo and Malaysia’s passing networks have different circumstances, with Vissel Kobe being the better team than Tokyo and Malaysia being the favourites against Timor-Leste. But Malaysia’s match against Timor-Leste also allows for a better look at their shape in possession since…they had a lot of possession.

Quoted from the ASEAN Cup Diary, day 3:

Malaysia also went out with a 3–2–5 build-up shape with the intention of controlling possession. Given that Timor-Leste was happy to just sit back in a mid/low 5–4–1 block, they were able to achieve just that. They had right-back (#2) Declan Lambert stayed deep to create a back-three with the centre-backs, while central midfielders (#21) Daniel Amier and (#16) Ezequiel Agüero formed the double pivot that sat just behind the opposition’s lone striker. Lambert also played as an inverted full-back to allow right winger (#11) Najmuddin Akmal to stay wider and take on Timor-Leste’s left-back.

I think that perfectly encapsulates the most noticeable trend shown on the passing network. Furthermore, Cklamovski can also recreate the two-man striker duo with Paulo Josué and either Darren Lok or Fergus Tierney since all three are natural strikers and have the tendency to make runs in behind. Should the Australian manager looks to have his keeper play long passes towards the attackers like how Taishi Brandon Nozawa did for Diego Oliveira against Kobe, it will not be a hard challenge to implement something similar.

Cklamovski will have to change the way that Malaysia are playing because their current focus is dominating possession and playing through the opposition under Pau Martí. Even against a stronger opponent like Thailand, they still had 49% of possession while they had 54% and 73% of the ball against Cambodia and Timor-Leste respectively. With FC Tokyo, however, their average possession percentage from last season was 48.5% and they only ranked 13th in the league. This means Cklamovski will bring a different style of football to Malaysia that will not focus on dominating the ball all the time.

In possession

One problem that Tokyo faced last season, as described by Ryo Nakagawara in his J1 League mid-season review, was that Tokyo tried to play a style that looked like a mix of everything whenever they had the ball.

The team is a weird mix of trying to play a more possession-based style and yet looking far more dangerous in transition, especially in the chaotic last ten-or-so minutes of games. Tokyo look far more comfortable playing out the back compared to previous years which is nice… but they don’t actually seem to progress the ball much at all and Tokyo certainly don’t take enough shots or even quality ones. — Ryo Nakagawara

This is true, because Tokyo took the 4th-least shot in the J1 League last season with just only 11.4 shots per game and their xG per game is the 5th-lowest with 1.207 xG per game. It is a weird dynamic because, for some reason, they are tied in 6th for goals scored per game with 1.4 goals per game and they are 2nd for shot accuracy with 12.2%. So they are not overperforming expectation by much, but they also do not take enough shots and still among one of the better teams for scoring goals?

But it is possible to see why Tokyo was able to score a lot of goals, because a lot of their goals were created and scored inside or on the edge of the 18-yard box. A decent number of those goals were of decent quality as well, especially the ones created to the right-hand side of the box. So, at least, it can be something positive that Cklamovski will bring to Malaysia, which is the persistence to get the ball into the penalty box and find good goal-scoring positions.

But Tokyo did rely slightly on one player to score goals, which was Araki, as pointed out in Ryo’s mid-season review. The gap between Araki and other teammates is not big, however, because three other attackers in striker Diego Oliveira, winger duo Teruhito Nakagawa and Endo had six and five goals respectively. The problem arises when you look at the xG difference since Araki and Endo overperformed by 1.863 xG and 1.862 xG respectively. Meanwhile, Diego Oliveira underperformed by almost a goal (-0.946 xG to be exact), which is not a good sign when your striker is underperforming his xG. So, yes, you can technically say that there is a reliance on Araki and Endo to provide the goals.

Of course, the young winger [Kota Tawaratsumida] isn’t helped by the fact that Tokyo don’t seem to have much of a plan after getting into the final 3rd from their build-up play. — Ryo Nakagawara

This is the part that concerns me the most because…Malaysia are facing almost the exact same problem. In both matches against Cambodia and Timor-Leste, whenever the opposition sat deep, Malaysia just seemed to get stuck and had no ideas on how to break the low block down. They pretty much relied on crosses into the box and hoped that one of the attackers would get to the end of those crosses and scored.

A positive thing, which is similar to FC Tokyo, is that they are also creating a lot of chances and scoring most of their goals inside of the box. The downside, though, is that there are also a lot of X shapes inside of the box, so even though they can get the ball into the area, they have not been that good at converting chances, or at least, hitting the target. Tierney is still young so his shooting ability can improve over time, but both Lok and Josué are already in their mid-30s and Cklamovski cannot rely on them to deliver goals for the long run, especially since the Asian Cup qualifying campaign will start soon.

I am also inclined to agree with Ryo regarding Tokyo’s reliance on wing attacks and how they use such attacks to put their wingers into situations where they can take on the opposition’s full-backs. A lot of Tokyo’s passes into the final third last season were aimed towards wide spaces or half-spaces, especially down the left-hand side, where the wingers were most likely to be located. Even though I have lowered the successful passes’ transparency on the visualisation below, it is still possible to notice areas that have been covered in green on both flanks.

This will not be that unfamiliar to Malaysia because they have already done that in this year’s ASEAN Cup. Against Timor-Leste, a lot of their build-up sequences looked to play through the opposition’s 5–4–1 mid-block, only to then played the ball wide for either left-back Daniel Ting or right winger Najmuddin Akmal. From there, the winger would look to take on the opposing full-back by themselves, or there would be a small passing combination between the full-back and the winger to get either of them to the byline with the ball for a subsequent cross or a cutback.

If this sounds familiar, because it is, and this is also how Ange’s team like to play. Currently at Tottenham, Timo Werner, Dejan Kulusevski, and Brennan Johnson are playing in almost similar roles. They look to stay wide, receive the ball, take on the full-backs to cut inside, and find opportunities to score goals. And it just so happens that two of Tokyo’s top four scorers are also wingers (Endo and Nakagawa), and, I do not think this is a coincidence, that both players were a part of Ange’s Yokohama F. Marinos team that won the J1 League in 2019. Expect something similar from players who will play as wingers for Malaysia, like Akmal or Fazrul Amir.

What fascinates me, though, is that quite a few of Tokyo’s key passes into final third are not aimed out wide, but instead aimed towards the area right in front of the D of the penalty box. I have not watched any footage of Tokyo from this season, so I can only assume that these passes are aimed towards Diego Oliveira, who might have been able to hold up the ball and free up the wingers to make runs in behind. Instead, Oliveira just took shots all by himself because he is a foreign striker, so there would have been a reliance on foreign strikers to score goals not just in Japan.

Since Malaysia is not a strong national team in Asia, Cklamovski will have plenty of opportunities to implement a style of play that relies on transitions. This can work against stronger teams like Japan, South Korea, or Australia like how Tokyo came out unbeaten against Vissel Kobe both times last season. But in order for them to thrive and get more favourable results, they will have to also be competent with playing more with the ball and break down low blocks against weaker teams like Timor-Leste.

It seemed as if Cklamovski was already trying to implement something at Tokyo but did not have enough time to find a perfect balance between a possession-heavy style and a transition-heavy style. Maybe, just maybe, we might be able to see a more complete style once he arrives at Malaysia. It is also possible that Cklamovski will utilise what is being done by Pau Martí and build upon what the Spanish caretaker has done.

But, in general, it is expected that under the guidance of Cklamovski, Malaysia will be more of a transitional side that relies on wing attacks to get into the final third. They will also be utilising long passes to encourage wingers to make runs in behind or send the ball to the lone striker to hold up the play. There will also be elements of a possession-based style, but I am not sure to what extent and how often will Cklamovski use such style. A problem that the Australian manager will have to fix, however, is Malaysia’s ability to create high-quality chances and score goals. Will Cklamovski relies on a few players to provide goals through their individual ability, or will he finds plans to get players into good goal-scoring positions? Time will tell, but his Tokyo side from last season suggests that it will be the former.

Set pieces

Evidence suggests that Tokyo was not a side that relied too heavily on set pieces. They only ranked 12th for corner kicks attempted with 183 in total over the 2024 season, but they have scored 13 goals from set plays, which took up 24.53% of their total goals distribution. They have also only generated shots from 23.2% of set piece situations, which is only ranked 19th in the league.

Interestingly, even though they did not generate any assists directly from corners, they did make 31 key passes from such situations. Their strategy was to send the ball into the central area of the penalty box, with 74% of first contacts were made directly in front of or near the goal, and only a combined 12% of the contacts were made close to the near or far posts. They might have utilised the height advantage of their players to win more aerial challenges in the box, which led to more goals being scored from set plays.

However, do not expect Malaysia to rely on set pieces to create chances. They have not scored from any set piece situations so far in the ASEAN Cup so it will not be something out of the ordinary.

Out of possession

It might not be right to continuously apply Ange’s style of play on Cklamovski’s Tokyo side and use that as a baseline for comparison, but it is one of the easier ways to identify what Cklamovski wants from his team and then rebuff any expectations that Cklamovski will just be doing similar stuff to Postecoglou.

With that in mind, one of the first defensive aspects that many tend to think about Ange’s team is how they press the opposition. There seems to be a suggestion that Tokyo did try to win possession high up the pitch based on the zones where they won possession, with the focus being moving the opposition wide and regaining possession out wide. It is also quite normal to see more possession being won closer to their own goal, but the low percentages of possession won inside of the final third (last two zones to the right) might suggest their press might not be that effective.

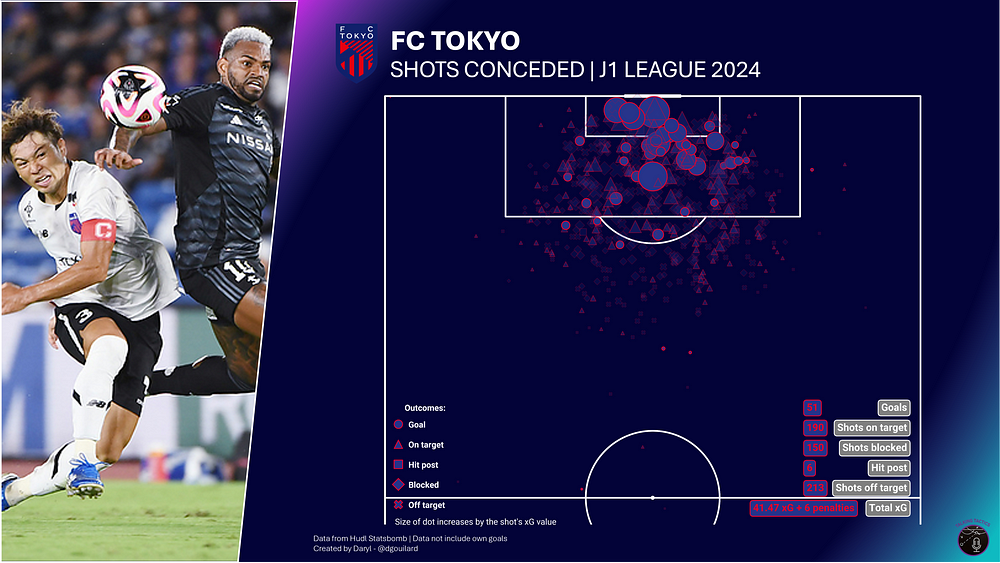

According to Football-Lab, their possession gain rate from their high press and counter press are only 31.1% and 32.6% respectively, putting Tokyo firmly among the bottom teams on this aspect. Their shot conceded rate from their high press and counter press are at 10% and 11.9%, which is the second-worst and third-worst in the league. Their average PPDA (opposition’s passes per defensive action) is also the second-worst in the league at (approximately) 7.65. All stats seem to point to the fact that Tokyo was not very good with their pressing and allowed the opposition a lot of time on the ball and plenty of opportunities to generate a shot afterwards.

Football-Lab also pointed out that Tokyo tended to defend in a slightly narrow shape as the width of their defensive block fluctuated slightly from 39.2 metres as a high block down to 37.2 metres as a low block. Cklamovski also preferred to use a slightly high defensive line, with their backline height throughout a match averaging out to 45.7 metres. This can present a potential problem for Malaysia since Tokyo played with a slightly narrow defensive shape and a high backline, but without a lot of end product with their press.

This explains the high volume of shots on target and goals that Tokyo conceded inside of the penalty box, which the stats (4.9 shots on target conceded per game, 4th-worst in the league) also agreed. Having a goalkeeper who might have prevented a decent amount of goals in Taishi Brandon Nozawa helped Tokyo a lot as he was forced to make a lot of saves (3.6 saves per 90, tied for 7th for all goalkeepers in the league), in which he successfully saved quite a few (74.6% save success rate, 8th in the league). A goalkeeper making a lot of saves throughout a season is already a sign that a team’s defence might not be good, and Tokyo’s defence must have benefited a lot to keep their goal conceded tally down to just 51.

High quality defenders are not something that Malaysia can bring to the table, and finding a goalkeeper who can overperform like Nozawa in Malaysia is even a tougher task. Hopefully, this will force Cklamovski to rethink his defensive approach that have conceded more than a goal per game for Tokyo and fix some of the existing problems in his defensive structure. As long as they do not have to rely on a goalkeeper to overperform and save the day, it can potentially lay out a solid foundation that Malaysia can use to improve their attack.

Conclusion

While there are some flaws and weaknesses that have been highlighted above, Peter Cklamovski can be a slight upgrade for Malaysia and present something different to how they are currently playing under Pau Martí. The team will have to change and things might take a bit of time to adapt, since they will be moving from a possession-heavy style to a transition-focused style.

Cklamovski will also have to address some of his defensive weaknesses as well since, at the international level, you just cannot afford to concede a lot of goals and rely on some individuals to help you get back into the game. I will choose to remain cautiously optimistic about Cklamovski’s move to Malaysia because there are still some flaws that needed to be fix. But if things work out for him, it can potentially be a success for both Malaysia and Cklamovski.

Originally published at https://www.talking-tactics.com.